"Inevitably, valuing a cultural landscape involves valuing the intangible as well as the tangible, the real as the magic, the popular as the courtly; in general, to dive into the enjoyment of life itself, rather than to have pleasure in its most enlightened and successful manifestations. "Rubén Pesci.

The Colca Canyon is an impressive geological feature located in the department of Arequipa in southern Peru. With its 3250 meters, is two and a half times deeper than the Grand Canyon in the USA (1400 meters) and is the second deepest canyon in the world, only surpassed in depth by the Cotahuasi Canyon (3535 meters), also located in Arequipa. The condor, Andean bird whose wingspan is the longest planet, often flyes over the vast abyss, as a majestic spectator of this incredible landscape.

This extraordinary gorge houses diverse climates and ecological niches and has allowed the development of different species, which accounts for the conservationist Mauricio de Romaña (Romaña and Carlos Zeballos Barrios greatly encouraged the "rediscovery" of the Canyon, through studies and the publication of guidebooks).

Ancient cultures like the Collaguas have lived in the Colca Valley, transforming it into an impressive cultural landscape, sculpting the impossible slopes of the Andes with terraces and villages (as Carl Sauer defined in his "Morphology of Landscape" (1925), the cultural landscape is the interaction of one social group over a natural landscape. Culture is the agent, nature is the environment, the cultural landscape is the result.)

After the Spanish conquest the inhabitants of the Colca were grouped in "reducciones" to form villages that settled on both sides of the valley, establishing a spatial network and economic organization of the territory that has been studied by experts like Dr. Maria Rostworowski and the archaeologist Steve Wrenkle and CIARQ .

After the Spanish conquest the inhabitants of the Colca were grouped in "reducciones" to form villages that settled on both sides of the valley, establishing a spatial network and economic organization of the territory that has been studied by experts like Dr. Maria Rostworowski and the archaeologist Steve Wrenkle and CIARQ .

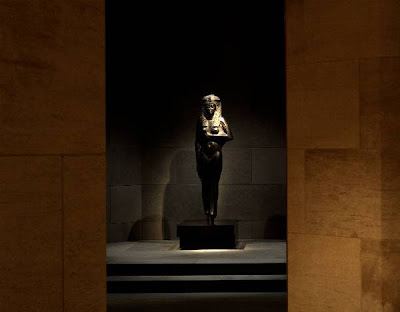

The churches of the Colca Valley are among the most important in South America, as host superb samples of colonial art. Ramon Gutierrez has published an interesting study of colonial architecture in the Colca and the AECI (Spanish International Cooperation Agency) has been implementing various projects of restoration and preservation in an interesting program which trains local people in the techniques for managing their own cultural heritage.

THE COLCA LODGE HOTEL

As a privileged spectator of this magnificent landscape, the Colca Lodge Hotel is located, designed by renowned Peruvian architect Álvaro Pastor.

Pastor was raised in Tucumán, Argentina and worked alongside his compatriot Henri Ciriani Paris. He has a prolific career which has been awarded nationally and internationally, including a first place in the academic competition for a Machu Picchu museum , undertaken along with architects G. Valdivia, E. Suarez, H. Perochena and R. Borda. He is a Proffessor at the Faculty of Architecture at the Catholic University of Arequipa.

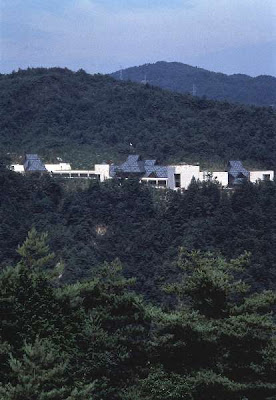

Pastor owns a unique sensitivity for the material and place in which his projects are located, without losing the characteristic language of contemporary architecture. This respect for the locus has led him to desing the Colca Lodge hotel using construction methods of the inhabitants of the valley, such as stone, clay, mud bricks, wood and straw, without losing the delicacy in the detail and the warm comfort that this facility required.

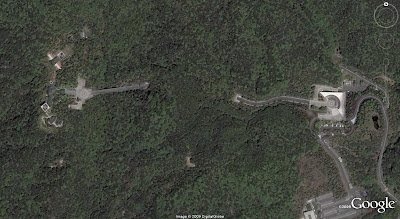

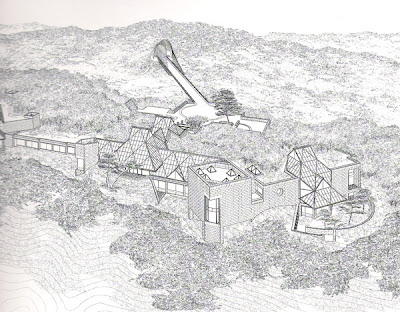

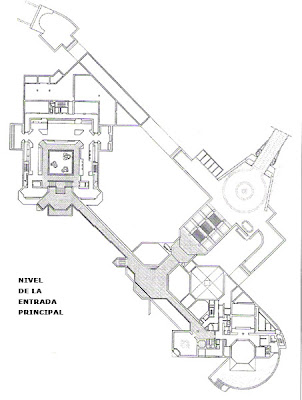

The hotel is located between the villages of Coporaque and Ichupampa, settled on a small plateau in front of the Colca River, extending as an extension of the terraces that sculpt the hillsides, just as the did 1500 years ago.

The complex has taken as reference the local traditional architecture, and in fact the hotel resembles a small Andean village.

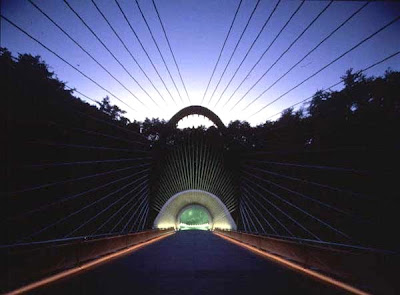

The heart of the Colca Lodge is the restaurant, a solid stone cube that overlaps another glass cube covered by a pyramid of straw.

In the opposite side is the a circular plaza, called the square of the moon, named after the old custom of observing the moon reflected in small ponds.

The rooms, by way of houses, are organized into two bars arising from this center, linked by the paved "streets". These volumes (one of them is semicircular) harmonize with the topography and surrounding terraces.

The cottages, which differ rhythmically in height, are separated from the public space by an entrance foyer. At the end of each volume there is a two-story module, corresponding to the suites.

The interior of the rooms expresses with supreme simplicity, the Andean vernacular architecture, but at the same time it offers a pleasant spatial arrangement.

As for the suites, Pastor proposes a social area located on the first level, consisting of a small lounge and kitchenette, with a expansion to a terrace and a private pool.

Thus, the architect favors the location of the bedroom on the second floor, offering guests a spectacular view of the valley.

The hotel takes advantage of the many hot springs located in the vicinity, product of volcanic activity in the area. However, they have been carefully designed not to interfere with the natural environment, as the architect used a system of canals similar to those that the Collaguas used in the past.

The design of the suites include private pools, ideal for enjoying the hot springs in the moonlight or at dawn, due to the thin, unpolluted air.

For the construction of this hotel Alvaro Pastor had the support of Berolatti Marcello , who is also a Peruvian architect who has been experimenting with traditional construction methods for several years.

The Colca Lodge redefines the syntax of and vernacular architectural re-composed in a contemporary and comfortable organization, humbly and masterfully integrating itself to the landscape.